The Macroscopic History of the Microscopic Septet

“Oh, how we’ve missed the Microscopic Septet! Back in the early 1980s, when jazz, on all aesthetic levels, seemed to be resolidifying its connection with its heritage, these wild and wooly virtuosos leapt into the breach between “outside” and “inside” jazz and made a cheerful shambles. They were as clever as the Beatles, as subversive as Captain Beefheart, as antic as Spike Jones. Did I mention that they were—and are—more fun than any other well-dressed jazz ensemble in the western world? …fans still light candles for their return. … Hurry back, fellows, won’t you? The uptown neoclassicists still have a lot to learn from you downtown pranksters.”

Gene Seymour, Newsday: The Long Island Newspaper, June 13, 2000

“Posterity is going to remember the Microscopic Septet as one of the best bands of the 1980s.”

Frances Davis, The Philadelphia Inquirer, August 25, 1988

The music of The Microscopic Septet was the sound of jazz in 20th-century America: all of it, from Ellington to Ayler, bebop to Zorn, Dixieland to experimental, captured in a microcosm. It distilled the essence of jazz as a popular music into a sound that swung, a music that was intelligent, sometimes smart-aleck, and always good clean fun. Optimistic and upbeat, full of innocent confidence, the Microscopic Septet captured not only the sound of jazz, but also the sound—or soundtrack—of 20th Century America. No wonder, then, that when National Public Radio (NPR) needed a new theme song for one of its most popular shows, Fresh Air with Terry Gross, broadcast to every home in America, it asked this band to compose the tune and has used it ever since.

The music of The Microscopic Septet was the sound of jazz in 20th-century America: all of it, from Ellington to Ayler, bebop to Zorn, Dixieland to experimental, captured in a microcosm. It distilled the essence of jazz as a popular music into a sound that swung, a music that was intelligent, sometimes smart-aleck, and always good clean fun. Optimistic and upbeat, full of innocent confidence, the Microscopic Septet captured not only the sound of jazz, but also the sound—or soundtrack—of 20th Century America. No wonder, then, that when National Public Radio (NPR) needed a new theme song for one of its most popular shows, Fresh Air with Terry Gross, broadcast to every home in America, it asked this band to compose the tune and has used it ever since.

Active from 1980–1992, The Microscopic Septet was part of New York’s emerging Downtown Music Scene, a diverse group of artists on the fringes of jazz, rock, and improv that would converge in the Knitting Factory when the club opened in 1987. But while the band shared an aesthetic for breaking down genres boundaries with such other Downtown bands as Curlew, Massacre, and Material; shared the goal of creating intelligent music that could be danced to with Curlew, and shared stylistic surface elements (retro sound, stage costumes and attitude) with the Jazz Passengers and Lounge Lizards, the Micros, as the band was familiarly called, neither sounded like nor was directly comparable to any one of the Downtown bands. More inclusive than even the barrier-breaking downtown crowd, the Micros shared elements with all these bands—and more.

CRISS CROSS

During the 1980s, jazz in New York City was split into two distinct scenes. Downtown’s jazz scene was unregimented, avant in outlook, and inclusive in scope, often merging with the rock scene and including improvisers, the free-jazz players, and the new jazz-funk/groove-influenced players. Mainstream jazz was headquartered Uptown, where Grammy Award-winning trumpeter Wynton Marsalis was reviving early forms like swing and bebop, enforcing a return to stylistic tradition, and championing jazz as America’s new classical music. As Will Friedwald noted “While the two major strains of ’80s jazz were “neo-classical” (ala Wynton Marsalis) and the avant garde, the Micros seemed to be doing both at the same time.” As NYU dropout and Micros’ founder Johnston said: “Break all the rules and respect all the saints.” Like Uptown, the Micros played swing music and quoted from the Masters. But they extended swing into the present, bringing free blowing from the lofts and Knitting Factory noise into the dance hall, and introducing the radio age to TV theme songs. As Johnston relayed in an interview with Howard Mandel: “…our music, if nothing else, is definitely jazz… Jazz is something that’s always changing, so of course our music is different than the way it was in the Fifties. It incorporates all the things we’ve experienced.”

As the Micros asserted in interviews, jazz began in the 1920s as a popular music, inclusive in its form. Danceable and approachable, it embraced the life around it, incorporating Latin rhythm, tango, polka and more. Later jazz, whether avant or traditional, became a ‘serious’ art form, aloof and apart. Johnston said in interviews:

“What the Micros are about…is that jazz went through a period of being an entertaining, popular music as it was in the twenties, thirties, and forties, to bop to eventually being this serious cult art music. Jazz for us is more than that, it is music we love and want to have fun with, which should not take away from our real reverence for the music.”

In the ’80s, jazz purists had frozen traditional jazz forms in time, cast them in bronze, and confined them to Uptown museums. The Micros brought Uptown jazz back Downtown, where together they had a good time, broke all the rules, and spawned the smiling future of the genre. Sounding like no one else, the Microscopic Septet was the only living jazz band in 1980s/90s NYC that was playing traditional jazz—swing music—and keeping it ‘real,’ extending it into the future. Ironically, while purists feared that the Micros were undermining traditional jazz, the band had done the opposite. “Surrealistic Swing”—the music of the Microscopic Septet—was the jazz swing music of the late 20th Century.

REFLECTIONS

The Microscopic Septet was founded in 1980 by Phillip Johnston, a composer, soprano saxophonist, and improvisor on NYC’s Lower East Side. Largely self-trained as a musician, Johnston was influenced by a pantheon of jazz and avant-rock greats that included Steve Lacy, Thelonius Monk, Duke Ellington, Captain Beefheart, and more, as well as by popular music in myriad forms. At the time he founded the Micros, he was co-leading the Public Servants (with vocalist Shelley Hirsch), a rock band that combined pop, funk, swing, Beefheart, and avant-garde performance art, and playing in Noise R Us, a large punk/funk band with a four-sax front line. Johnston was also playing in a quartet and septet led by composer and pianist Joel Forrester. Johnston recruited musicians from these and other bands to assemble a saxophone-quartet-plus-rhythm-section jazz band. He brought Forrester on as co-leader, sharing half of the composing responsibilities. The Microscopic Septet’s first line-up also included Dave Sewelson (baritone sax; Noise R Us & Public Servants), George Bishop (tenor sax; Noise-R-Us), John Zorn (alto sax; Public Servants), Dave Hofstra (bass; Public Servants) and Bobby DeMeo (drums). By the time the band played its first show at the Lower East Side’s Ear Inn, on February 22, 1981, Richard Dworkin was in the drummer’s seat, having replaced DeMeo, and John Hagen had replaced Bishop on sax. When Zorn left to pursue an independent career, Don Davis joined the Micros on alto sax. Paul Shapiro replaced Hagen after the Micros first lp, Take the Z Train, was released. The band’s lineup remained remarkably stable afterwards.

The Microscopic Septet was founded in 1980 by Phillip Johnston, a composer, soprano saxophonist, and improvisor on NYC’s Lower East Side. Largely self-trained as a musician, Johnston was influenced by a pantheon of jazz and avant-rock greats that included Steve Lacy, Thelonius Monk, Duke Ellington, Captain Beefheart, and more, as well as by popular music in myriad forms. At the time he founded the Micros, he was co-leading the Public Servants (with vocalist Shelley Hirsch), a rock band that combined pop, funk, swing, Beefheart, and avant-garde performance art, and playing in Noise R Us, a large punk/funk band with a four-sax front line. Johnston was also playing in a quartet and septet led by composer and pianist Joel Forrester. Johnston recruited musicians from these and other bands to assemble a saxophone-quartet-plus-rhythm-section jazz band. He brought Forrester on as co-leader, sharing half of the composing responsibilities. The Microscopic Septet’s first line-up also included Dave Sewelson (baritone sax; Noise R Us & Public Servants), George Bishop (tenor sax; Noise-R-Us), John Zorn (alto sax; Public Servants), Dave Hofstra (bass; Public Servants) and Bobby DeMeo (drums). By the time the band played its first show at the Lower East Side’s Ear Inn, on February 22, 1981, Richard Dworkin was in the drummer’s seat, having replaced DeMeo, and John Hagen had replaced Bishop on sax. When Zorn left to pursue an independent career, Don Davis joined the Micros on alto sax. Paul Shapiro replaced Hagen after the Micros first lp, Take the Z Train, was released. The band’s lineup remained remarkably stable afterwards.

The new band’s name—Microscopic Septet—alluded partially to the composers’ desire to create big band arrangements and orchestrations for a smaller group. Said Johnston: “The instrumentation is enough to give us a big range of colors and work compositionally in a more expansive way.” It worked, DownBeat noted, as ”the septet often fools you into thinking that there are four or five more horn players hiding under the chairs.” But the name also described their compositions, which evoked entire eras of music through snips of tango or other tell-tale refrain. As the New York Times stated: “The Microscopic Septet stands out…primarily through its command of idiomatic detail—the group summons the sound of an Ellington orchestra, or the feel of a 50’s rhythm-and-blues band, with a few well-chosen phrases and sonorities.”

The new band’s name—Microscopic Septet—alluded partially to the composers’ desire to create big band arrangements and orchestrations for a smaller group. Said Johnston: “The instrumentation is enough to give us a big range of colors and work compositionally in a more expansive way.” It worked, DownBeat noted, as ”the septet often fools you into thinking that there are four or five more horn players hiding under the chairs.” But the name also described their compositions, which evoked entire eras of music through snips of tango or other tell-tale refrain. As the New York Times stated: “The Microscopic Septet stands out…primarily through its command of idiomatic detail—the group summons the sound of an Ellington orchestra, or the feel of a 50’s rhythm-and-blues band, with a few well-chosen phrases and sonorities.”

BRILLIANT CORNERS

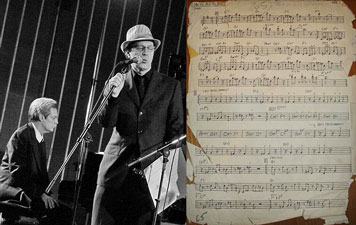

The team-up of Johnston and Forrester as the Micros’ composers proved to be magic; their compositions became the band’s stars. Called “the boldest and most gifted pair of composers to have joined forces in one group since Roscoe Mitchell and Joseph Jarman of the Art Ensemble of Chicago” [Philadelphia Inquirer], the two had known each other since the early 70s, and shared the same musical aesthetics, humor, and similarly skewed world views. They had met, says Johnston, when he was living in the Bowery, and Forrester, hearing music, barged into his apartment, unannounced: “I was playing a Thelonious Monk tune, and a guy I had never seen before came walking through my door, which wasn’t locked—those were the hippie days…” Not surprisingly, humor would play a role in the Septet, emerging in Johnston’s and Forrester’s compositions and in their onstage banter. The Micros would prove that technically sophisticated music could also be funny, and fun.

The team-up of Johnston and Forrester as the Micros’ composers proved to be magic; their compositions became the band’s stars. Called “the boldest and most gifted pair of composers to have joined forces in one group since Roscoe Mitchell and Joseph Jarman of the Art Ensemble of Chicago” [Philadelphia Inquirer], the two had known each other since the early 70s, and shared the same musical aesthetics, humor, and similarly skewed world views. They had met, says Johnston, when he was living in the Bowery, and Forrester, hearing music, barged into his apartment, unannounced: “I was playing a Thelonious Monk tune, and a guy I had never seen before came walking through my door, which wasn’t locked—those were the hippie days…” Not surprisingly, humor would play a role in the Septet, emerging in Johnston’s and Forrester’s compositions and in their onstage banter. The Micros would prove that technically sophisticated music could also be funny, and fun.

For the Microscopic Septet, Johnston and Forrester envisioned writing music that would capture jazz’s essence: fluid and inclusive, a popular music that was joyful and danceable (ie. a music that swung). They wanted to break away from then-standard head-solo-head song formats and instead write extended, layered jazz compositions that segued different themes in a single piece, as Duke Ellington and Jelly Roll Morton had done. Their extended compositions would assimilate the entire history of jazz, as well as other popular music from the soundtrack of their lives, from polkas to Latin tangos to cartoon ditties to klezmer to TV theme songs to New Wave. “We all came out of the type of music played by the Art Ensemble of Chicago and Anthony Braxton, as well as bebop. But we were playing standards, Dixieland and rock to make a living”, said Johnston in various interviews. “We …grew up listening to pop. What we try to do is get to the heart of all these different musics.” Johnston and Forrester adhered to one stylistic rule: “It’s gotta swing, whether its Latin or R&B or straight-ahead blowing. …But swing—that’s the foundation of what we do.” The Micros, asserted Johnston, “…play music that swings, that has beautiful harmonies and melodies, and everything else is really second to that. The ideas that have always run through jazz—of swinging, of telling a story, of being real—to me that’s at the essence of everything we try to do.”

For the Microscopic Septet, Johnston and Forrester envisioned writing music that would capture jazz’s essence: fluid and inclusive, a popular music that was joyful and danceable (ie. a music that swung). They wanted to break away from then-standard head-solo-head song formats and instead write extended, layered jazz compositions that segued different themes in a single piece, as Duke Ellington and Jelly Roll Morton had done. Their extended compositions would assimilate the entire history of jazz, as well as other popular music from the soundtrack of their lives, from polkas to Latin tangos to cartoon ditties to klezmer to TV theme songs to New Wave. “We all came out of the type of music played by the Art Ensemble of Chicago and Anthony Braxton, as well as bebop. But we were playing standards, Dixieland and rock to make a living”, said Johnston in various interviews. “We …grew up listening to pop. What we try to do is get to the heart of all these different musics.” Johnston and Forrester adhered to one stylistic rule: “It’s gotta swing, whether its Latin or R&B or straight-ahead blowing. …But swing—that’s the foundation of what we do.” The Micros, asserted Johnston, “…play music that swings, that has beautiful harmonies and melodies, and everything else is really second to that. The ideas that have always run through jazz—of swinging, of telling a story, of being real—to me that’s at the essence of everything we try to do.”

’ROUND MIDNIGHT

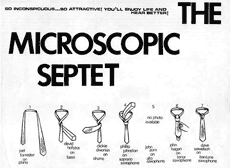

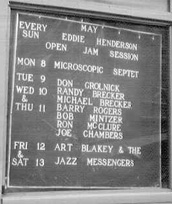

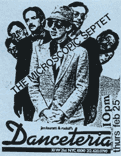

A late-20th-century swing band steeped in dancehall tradition, The Microscopic Septet thrived on live performance. “We were all about playing,” says Johnston; “all we really wanted to do was have a good time and play the best music we could imagine, the best we knew how.” It played the Downtown music scene circuit—rock clubs like CBGB, Mudd Club, Danceteria, Peppermint Lounge, Studio Henry, Acme Bar and Grill and more. Later, it played the Knitting Factory and such mainstream jazz clubs as The Blue Note, as well as jazz festivals worldwide (JVC Jazz Fest). These performances attracted a devoted cult following as much for the music—technically sophisticated and played by top-notch musicians—as for the on-stage antics. The band wore suits and ties onstage, as a respectful tip ’o the fedora to Uptown’s jazz traditionalists as well as a wink to stylish New Wave rockers with skinny ties. (A poster announcing the band’s first show depicted its lineup as the seven steps to tie a necktie, and New York Rocker would later refer to them as “Seven Men in Neckties” in a review.) Like the Sun Ra Arkestra, its performances were legendary not only for musical substance, but also for entertainment value. Live renditions of one favorite tune, “Lobsters on Parade,” featured besuited Micros donning tasseled fezzes and parading through the audience.

A late-20th-century swing band steeped in dancehall tradition, The Microscopic Septet thrived on live performance. “We were all about playing,” says Johnston; “all we really wanted to do was have a good time and play the best music we could imagine, the best we knew how.” It played the Downtown music scene circuit—rock clubs like CBGB, Mudd Club, Danceteria, Peppermint Lounge, Studio Henry, Acme Bar and Grill and more. Later, it played the Knitting Factory and such mainstream jazz clubs as The Blue Note, as well as jazz festivals worldwide (JVC Jazz Fest). These performances attracted a devoted cult following as much for the music—technically sophisticated and played by top-notch musicians—as for the on-stage antics. The band wore suits and ties onstage, as a respectful tip ’o the fedora to Uptown’s jazz traditionalists as well as a wink to stylish New Wave rockers with skinny ties. (A poster announcing the band’s first show depicted its lineup as the seven steps to tie a necktie, and New York Rocker would later refer to them as “Seven Men in Neckties” in a review.) Like the Sun Ra Arkestra, its performances were legendary not only for musical substance, but also for entertainment value. Live renditions of one favorite tune, “Lobsters on Parade,” featured besuited Micros donning tasseled fezzes and parading through the audience.

Johnston and Forrester were prolific composers; by the time the Micros disbanded, in 1992, it had a songbook of over 180 tunes. Only 34 of those were recorded and released in the band’s lifetime, in a total of 4 albums, all released on small labels to an impressive amount of high-profile critical acclaim. The Micros’ recordings received glowing reviews in big-city newspapers (New York Times, Chicago Tribune) and alternative papers (L.A. Reader, The Village Voice) on both coasts, as well as in major jazz publications (DownBeat, Cadence). Op and the subsequent Option, the bastions of hip alternative music in the ’80s and ’90s—equivalent to today’s The Wire—also favorably reviewed the Micros, as did such mainstream music publications as Musician and Billboard. Towards the band’s latter years, it was being praised enthusiastically in such widely-distributed general magazines as Interview, The New Yorker, Elle, GQ, and even Vanity Fair. The January/February 1990 issue of Option, featuring Laurie Anderson on its cover, devoted a full article to the Microscopic Septet.

UGLY BEAUTY

The band’s debut LP, Take the Z Train, came out on Press Records in 1983. Recorded “direct to two-track—basically the way they did it in the ’50s…[at] Seltzer Sound, where Eubie Blake recorded,” it featured cover art by San Francisco artist Bill Paradise and received an auspicious amount of press, including 4-star reviews in both DownBeat and the Rolling Stone Jazz Record Guide. Cadence exclaimed: “It is as if the entire history of improvisatory music is on parade…. recommended!" while New York Beat called it “the headiest collection of new swing music to come along in some time.”

The band’s debut LP, Take the Z Train, came out on Press Records in 1983. Recorded “direct to two-track—basically the way they did it in the ’50s…[at] Seltzer Sound, where Eubie Blake recorded,” it featured cover art by San Francisco artist Bill Paradise and received an auspicious amount of press, including 4-star reviews in both DownBeat and the Rolling Stone Jazz Record Guide. Cadence exclaimed: “It is as if the entire history of improvisatory music is on parade…. recommended!" while New York Beat called it “the headiest collection of new swing music to come along in some time.”

The following year, the Micros did its first 6-week tour of the Netherlands, home to Willem Breuker and the ICP Orchestra, artists to whom some compared it. It recorded its only live album, Let’s Flip!, which was released in 1985 by Dutch label Osmosis Records with liner notes by Richard Forman, a key figure New York’s avant-garde theatre scene. Let’s Flip! captured the excitement of the band live in concert in Rotterdam and received glowing reviews from DownBeat, Musician, and Billboard. Option called it “Good clean fun, recorded live.” A second tour of The Netherlands generated a studio recording, Off Beat Glory. Released by Osmosis in 1986, Off Beat Glory contained liner notes by American novelist William Kotzwinkle, author of The Fan Man. DownBeat remarked that “…these guys should be more famous than they are. Their music is well-written, their playing cooks, and everything they do is accessible…”

Beauty Based on Science was the band’s fourth CD, and last recording released during its lifetime. Recorded in NYC, it was released on Stash in 1988, and featured liner notes by ‘New York School’ poet, Ron Padgett, CD cover art by painter Bob Tuska, and cartoons by Collin Kellogg. It generated positive reviews not only in the music press, but also captured the interest of mainstream, general interest publications. Vanity Fair announced that “If they don’t watch their step, the Microscopic Septet, lovingly known as “the best New York band that hardly anybody’s heard of,” is going to have to change its tune….the Katzenjammer Kids of postmodernism have arrived.”

As the ’90s arrived, the Microscopic Septet was poised on the edge of mainstream success. In January 1990, it recorded several versions of a new theme song for NPR’s Fresh Air with Terry Gross, composed by Forrester, which have aired continually ever since. Also in 1990, the Micros recorded a single, “You Know What You Know,” the only recorded Micros vocal tune. Frances Davis, who had championed the band from its beginning, advocated for a Micros’ TV show:

“When I replace Letterman…the World’s Most Dangerous Bar Mitzvah Band has to go. The band I’m considering as a replacement is the Microscopic Septet, a New York saxophone quartet (plus rhythm) whose riff do what riffs are supposed to do: set your pulse racing and stick in your noggin for days on end. … So why aren’t these guys rich and famous, or at least universally adored by those in the know? …on the bandstand, their high-spirited humor is difficult to resist. This is a band that knows how to have fun while going deep, and one would think that, with proper exposure, that combination would give them widespread appeal. Somebody oughta put these guys on TV.”

Frances Davis, Outcats, Oxford University Press: 1990

EVIDENCE

In 2006, Cuneiform’s four-CD retrospective of the Microscopic Septet puts the spotlight back on a band that should have never left the stage. Called History of the Micros, this retrospective was released in two parts/volumes, each containing two CDs. It contains the music on all 4 of band’s albums, and an additional 11 tracks never released during the band’s lifetime. The CD artwork was by Pulitzer Prize winning New York cartoonist Art Spiegelman, creator of the graphic novel Maus.

In 2006, Cuneiform’s four-CD retrospective of the Microscopic Septet puts the spotlight back on a band that should have never left the stage. Called History of the Micros, this retrospective was released in two parts/volumes, each containing two CDs. It contains the music on all 4 of band’s albums, and an additional 11 tracks never released during the band’s lifetime. The CD artwork was by Pulitzer Prize winning New York cartoonist Art Spiegelman, creator of the graphic novel Maus.

Part 1, titled History of the Micros Volume 1: Seven Men in Neckties, covered the band’s early history, from 1980–85. It contained 2 CDs, featuring reissues of the band’s first LP, Take the Z Train; its second LP and only live album, Let’s Flip!; and several previously unreleased tracks, including live recording done at the same time as Let’s Flip! and and the most common version (“Evil Twin”, in minor key) of Forrester’s theme for NPR’s Fresh Air with Terry Gross.

Part 2, titled History of the Micros Volume 2: Surrealistic Swing, covered the years c. 1986–1990. It featured reissues of Off Beat Glory and Beauty Based on Science (The Visit), the band’s third and fourth release. It also included previous unreleased tracks from throughout the band’s career, including 2 tracks from an early recording by the band’s first lineup with John Zorn; an unreleased single with vocals by Paul Shapiro; the “Happy Twin”(in major key) of Forrester’s theme for Fresh Air with Terry Gross, and a different Fresh Air theme used during the First Gulf War of 1990–1991.

To celebrate the release of History of the Micros, the Microscopic Septet reunited for a tour in November and December 2006, including dates in both the U.S. and Europe. The two double-CD sets gained stupendous praise, attention and sales, and The Micros had such a good fun on the tour that they decided to make it ‘an occasional regular thing’.

WORK

Founder and co-leader Phillip Johnston desired to do a new recording; stating that “since we broke up with 180 mostly original tunes in our repertoire, I mourn the many great tunes that never got recorded.” Co-leader Joel Forrester stated that: “Going there in public didn’t call to me. But then we had this rehearsal, and I realized that the music this band plays is singular. I can’t make it with any other people.” In 2007, the Micros did a well-received, two week tour of Europe before returning to New York to record their first release in 20 years, Lobster Leaps In, released on Cuneiform.

Founder and co-leader Phillip Johnston desired to do a new recording; stating that “since we broke up with 180 mostly original tunes in our repertoire, I mourn the many great tunes that never got recorded.” Co-leader Joel Forrester stated that: “Going there in public didn’t call to me. But then we had this rehearsal, and I realized that the music this band plays is singular. I can’t make it with any other people.” In 2007, the Micros did a well-received, two week tour of Europe before returning to New York to record their first release in 20 years, Lobster Leaps In, released on Cuneiform.

The result was another excellent opportunity for longtime Micros fans to hear parts of the band’s catalog that had remained unperformed for years. Fans and critics received the new release warmly: Jazziz Magazine said the album brought “a renewed sense of fun to the often humorless jazz milieu,” while the Village Voice called the band “the finest retro-futurists around.” With this release the Micros continued their roughly annual reunion tour.

EPISTROPHY

The next chapter of the Microscopic Septet’s saga springs from events which occurred before the band’s formation.

As described above, in 1974, the Monk tune “Well You Needn’t” first brought the future Micros co-leaders together by chance. Johnston was living in the Bowery at the time, and Forrester, hearing music, barged into his apartment, unannounced: “I was playing a Thelonious Monk tune, and a guy I had never seen before came walking through my door, which wasn’t locked—those were the hippie days...” The encounter sparked a friendship and working relationship, in which Monk’s music reverberated on multiple levels across the years.

Another chance encounter—at chicken-and-ribs place West Boondock, forged Forrester’s friendship with the Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter. And through the Baroness, Forrester would ultimately meet and periodically play piano for Monk. Since Johnston and Forrester’s first meeting, Monk’s music has remained an inspiration and guiding light throughout their music careers.

In addition to creating and playing their own music, they always played Monk’s music with the Microscopic Septet, but due to their limited number of releases and their copious original songbook (more than 180 tunes), they only previously recorded one Monk composition.

CREPUSCULE WITH THELONIOUS

A new project would rectify that omission. Launched with the help of a fan-supported Kickstarter campaign, the Micros recorded and released original arrangements of twelve Monk tunes—half from “back in the day” and half newly-written—as Friday the Thirteenth: The Micros Play Monk.

A new project would rectify that omission. Launched with the help of a fan-supported Kickstarter campaign, the Micros recorded and released original arrangements of twelve Monk tunes—half from “back in the day” and half newly-written—as Friday the Thirteenth: The Micros Play Monk.

For this recording, the Microscopic Septet made clear their line of descent from Thelonious Monk. The humor and angularity of Monk’s compositions mesh easily and joyfully with the elaboration and juxtaposition of the Micros-style arranging. This was a true celebration of Monk by a group that could arguably be called his most sensitive and sensational heirs.

Featuring gorgeous art work by New Yorker artist Barry Blitt (the man responsible for the infamous and controversial Michelle and Barack “fist-bump”) and liner notes by jazz critic and long-time Micros fan Peter Keepnews, Friday the 13th was surprising yet inevitable: a long overdue party with the master, at which The Micros Play Monk.

Since its founding in 1980, the Micros have been responsible for some of the most captivating, memorable, and entertaining original tunes in the past 40 years of American jazz. Transcending mere tribute, the Microscopic Septet’s Friday the 13th distills Monk’s heady and humorous essence, revives his iconoclastic spirit, and revels in, and with, the creative compositions of Thelonious Monk.